Sobre os tumultos em Londres, que rapidamente se propagaram a outras cidades inglesas, vale a pena não só ler o texto de Nina Power, "As London Explodes in Riots, There Is a Context That Can't Be Ignored: Brutal Cuts and Enforced Austerity Measures", mas também a extensa e aprofundada análise de Reflections on a Revolution (ROAR) e que a seguir transcrevemos:

The riots spreading through London are a terrifying reminder of what lies ahead as the austerity-obsessed West nosedives into economic collapse.

The markets plummet and London burns. Whatever your political inclinations may be, there’s no denying the apocalyptic quality to the headlines coming out of Europe’s largest city right now. What we are witnessing is financial meltdown and social meltdown in tandem. And, while there is no direct causal relationship between the two historical moments, there’s a connecting theme that unites them in a complex dialectic of collapse.

So this is what things have come to: a societal tragedy of unfathomable proportions. What the UK is experiencing right now is the total breakdown of social cohesion into utter lawlessness and indiscriminate violence. On the third consecutive day of unrest, rioting and looting spread throughout the capital and — for the first time — to other UK cities as well. And while I hate to be gloomy, I have to remind you once again that this is only just the beginning.

With over 20 poorer neighborhoods in London convulsing in the flames of rage, and with the unrest spreading to disadvantaged areas in Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds and Bristol, this total breakdown of law and order has an undeniable structural quality to it. The explosion of anger and cynicism may have come as a complete surprise to the authorities, but locals have known this to be simmering beneath the surface for years — if not decades.

So when Boris Johnson, as Mayor of London, refers to the social unrest as ”nothing more than wanton criminality,” he engages in an extremely dangerous simplification. After all, violence is a complex phenomenon that arises from an intricate dialectic between behavioral/psychological (individual) factors on the one hand, and cultural/socio-economic (structural) factors on the other. It is in their complex interplay that we must look for answers.

The Structural Component

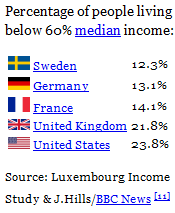

The United Kingdom has always been one of the most unequal and least socially-mobile societies in the Western world. Among continental Europeans, it is notorious for tolerating the existence of what Oscar Lewis has called an “underclass“, and what Marx referred to as the “lumpenproletariat“, or the “refuse of all classes” that continues to live an unproductive existence at the margins of society, excluded for all practical purposes from the basic functioning of the market system.

The numbers, in this respect, are telling. In 2003 and 2004, a whopping 21 percent of children in the UK grew up in households below the poverty line (after housing costs are taken into account, this rises to an incredible 28 percent). One EU study this year found that 17 percent of UK youths qualify as “NEETs” — Not in Employment, Education or Training, “in other words high-school dropouts with no prospects of employment.” The same study found that over 600,000 people under the age of 25 have never had a day of work.

While it would be ridiculous to use such statistics as a justification for the dangerous, irresponsible and anti-social behavior of the rioters, it would be just as foolish to simply ignore this crucial social context and only focus on the “aberrant behavior” of “deviant individuals.” The violence and thievery may be entirely indiscriminate and a-political, but the root causes of it are profoundly political and carry a very clear discriminatory component.

A society where an hour’s bus ride from Kensington to Newham takes you across a six year reduction in male life expectancy – from 78.5 years to 72.4 – is a profoundly sick society. The gap is actually bigger than the one between the US and Nicaragua, with the latter being the second poorest country in Latin America. London, in other words, may be the most expensive city in the world, but it literally contains a developing country within its city boundaries.

Even the pro-market Financial Times last year warned that “Britain must mind the gap”. Referring to a landmark government report, it wrote that “the UK suffers from high inequality,” and “saw a surge in its Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s. Since then, increased redistribution has managed to slow this process. But British inequality is a problem that will not disappear. It has deep roots and cannot be ignored.”

In their crucial book, The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett provide a wide array of statistical evidence to back up their claim that unequal societies tend to produce (in addition to a range of other social and medical problems) more violence and more crime. As a result of this, the UK prison population nearly doubled from 46,000 to 80,000 in the two short decades between 1990 and 2007.

The Individual Component

So how does this social reality affect the individual? The Guardian quoted criminologist John Pitts as saying that ”many of the people involved are likely to have been from low-income, high-unemployment estates, and many, if not most, do not have much of a legitimate future … Those things that normally constrain people are not there. Much of this was opportunism but in the middle of it there is a social question to be asked about young people with nothing to lose.”

The Individual Component

So how does this social reality affect the individual? The Guardian quoted criminologist John Pitts as saying that ”many of the people involved are likely to have been from low-income, high-unemployment estates, and many, if not most, do not have much of a legitimate future … Those things that normally constrain people are not there. Much of this was opportunism but in the middle of it there is a social question to be asked about young people with nothing to lose.”

While there is never any justification for selfish theft and wanton violence against innocent individuals, the looters find ways to justify their actions. “They feel they can rationalise it by targeting big corporations. There is a sense that the companies have lots of money, while they have very little.” Indeed, in a fascinating conversation caught on tape by the BBC, a couple of girls boasted that the riots are about “showing the rich we can do what we want.”

There are two crucial components to this seemingly simple sentence. First of all, there’s the powerful assertion of “doing what we want.” As Lukács put it, under the ruthless logic of the market, “the personality can do no more than look on helpless while its own resistance is reduced to an isolated particle fed into an alien system.” Violence becomes a psychological tool for breaking out of that hostile universe and reclaiming a sense of agency. In Pitts’ words, looting makes “powerless people suddenly feel powerful,” which is “very intoxicating”.

Secondly, there’s the overt class component that the BBC is still so desperately trying to hide. One doesn’t need to be a Marxist to follow this line of reasoning: class-based exclusion is closely tied to its cultural manifestation, what the anti-Marxist sociologist Pierre Bourdieu famously called symbolic violence. By this he referred to the patterns of speech, dress, consumption, etc., by which dominant groups express their cultural “superiority” over subordinate ones.

The psychological consequence of this symbolic violence is to produce a profound sense of social alienation within the individual — a sense that one has absolutely no stake in society’s dominant value system. This leads to a situation where the subversion of societal norms suddenly becomes a deceptively joyous act of “liberation”. Ironically, this process may have been further fueled by endless marketing campaigns promising “salvation through consumption“.

As Pitts puts it, this is a generation bred on a diet of excessive consumerism and bombarded by advertising. “Where we used to be defined by what we did, now we are defined by what we buy. These big stores are in the business of tempting [the consumer] and then suddenly these people find they can just walk into the shop and have it all.” As @DominicKavakeb tweeted, “if you keep telling people who can’t afford stuff to buy stuff, they might just end up taking stuff.”

A Regression — Not a Revolution

But that said, one thing needs to be made very clear: anyone who is still under the impression that this is a “protest” is gravely mistaken. This is not a revolution. If anything, it’s a major regression; a breakdown into mob rule. No one will benefit from this, except, perhaps, for the government itself. After all, the unfortunate fact that many of Britain’s poor tend to be ethnic minorities will allow Cameron to once again play the “death of multiculturalism” card.

Furthermore, as this brave West Indian woman pointed out, people don’t fight for a cause. The disturbances have long ceased to be protests against police brutality — they have descended into total chaos. In this environment, there is no hope of building a constructive movement for progressive social change. This was bound to happen, though. As a Greek friend predicted at Syntagma last month, “when the UK goes into revolt, it will be ugly.”

These riots are particularly ugly because the biggest victims so far have been the hard-working shop-keepers and average people who have become the innocent targets of indiscriminate aggression — the people who had to jump from their homes to escape the blaze, the people who lost their houses and their livelihoods through arson, theft and destruction. Why in heaven’s name would these angry youths target their own neighborhoods, instead of the rich ones?

While many people responded with shock and horror to a video displaying a bunch of thugs stealing from an injured man while pretending to assist him, psychologists have long had an explanation for this “inexplicable” behavior. As Wilkinson & Pickett write, ”when people react to a provocation from someone with higher status by redirecting their aggression onto someone of lower status, psychologists label it displaced aggression,” (The Spirit Level, p. 167).

The greatest tragedy is that this displaced aggression leaves the peaceful majority doubly affected: first by the economic exclusion and symbolic violence of the ruling social groups, and secondly by the displaced aggression of the disaffected youth in their own neighborhoods. And sadly, this pattern is likely to intensify over the coming years and decades, as financial collapse and fiscal austerity will combine to squeeze millions of Britons into poverty.

As the New York Times correctly pointed out, “for a society already under severe economic strain, the rioting raised new questions about the political sustainability of the Cameron government’s spending cuts, particularly the deep cutbacks in social programs.” After all, austerity measures “have hit the country’s poor especially hard, including large numbers of the minority youths who have been at the forefront of the unrest.”

In December 2010 we made a gloomy prediction for the new year: “The rage is spreading, and the legitimation crisis of global capitalism is only going to deepen in 2011 as austerity measures aggravate inequality, insecurity and unemployment. The question is not so much if there will be renewed violence, but where and when it will take place.” Austerity may not be the root cause of these riots — but it will be fuel on the fire of Britain’s ongoing social meltdown.

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário